As saint of our own time and as the first United States citizen to be elevated to sainthood, Mother Cabrini has a double claim on our interest. Foundress of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart and pioneer worker for the welfare of dispersed Italian nationals, this diminutive nun was responsible for the establishment of nearly seventy orphanages, schools, and hospitals, scattered over eight countries in Europe, North, South, and Central America. Still living are pupils, colleagues, and friends who remember Mother Cabrini vividly; her spirit continues to inspire the nuns who received their training at her hands. Since the record remains fresh in memory, and since the saint's letters and diaries have been carefully preserved, we have more authentic information about her, especially of the formative years, than we have concerning any other saint.

Francesca Cabrini was born on July 15, 1850, in the village of Sant' Angelo, on the outskirts of Lodi, about twenty miles from Milan, in the pleasant, fertile Lombardy plain. She was the thirteenth child of a farmer's family, her father Agostino being the proprietor of a modest estate. The home into which she was born was a comfortable, attractive place for children, with its flowering vines, its gardens, and animals; but its serenity and security was in strong contrast with the confusion of the times. Italy had succeeded in throwing off the Austrian yoke and was moving towards unity. Agostino and his wife Stella were conservative people who took no part in the political upheavals around them, although some of their relatives were deeply concerned in the struggle, and one, Agostino Depretis, later became prime minister. Sturdy and pious, the Cabrinis were devoted to their home, their children, and their Church. Signora Cabrini was fifty-two when Francesca was born, and the tiny baby seemed so fragile at birth that she was carried to the church for baptism at once. No one would have ventured to predict then that she would not only survive but live out sixty-seven extraordinarily active and productive years. Villagers and members of the family recalled later that just before her birth a flock of white doves circled around high above the house, and one of them dropped down to nestle in the vines that covered the walls.

The father took the bird, showed it to his children, then released it to fly away.

Since the mother had so many cares, the oldest daughter, Rosa, assumed charge of the newest arrival. She made the little Cecchina, for so the family called the baby, her companion, carried her on errands around the village, later taught her to knit and sew, and gave her religious instruction. In preparation for her future career as a teacher, Rosa was inclined to be severe. Her small sister's nature was quite the reverse; Cecchina was gay and smiling and teachable. Agostino was in the habit of reading aloud to his children, all gathered together in the big kitchen. He often read from a book of missionary stories, which fired little Cecchina's imagination. In her play, her dolls became holy nuns. When she went on a visit to her uncle, a priest who lived beside a swift canal, she made little boats of paper, dropped violets in them, called the flowers missionaries, and launched them to sail off to India and China. Once, playing thus, she tumbled into the water, but was quickly rescued and suffered only shock from the accident.

At thirteen Francesca was sent to a private school kept by the Daughters of the Sacred Heart. Here she remained for five years, taking the course that led to a teacher's certificate. Rosa had by this time been teaching for some years. At eighteen Francesca passed her examinations, , and then applied for admission into the convent, in the hope that she might some day be sent as a teacher to the Orient. When, on account of her health, her application was turned down, she resolved to devote herself to a life of lay service. At home she shared wholeheartedly in the domestic tasks. Within the next few years she had the sorrow of losing both her parents. An epidemic of smallpox later ran through the village, and she threw herself into nursing the stricken. Eventually she caught the disease herself, but Rosa, now grown much gentler, nursed her so skillfully that she recovered promptly, with no disfigurement. Her oval face, with its large expressive blue eyes, was beginning to show the beauty that in time became so striking.

Francesca was offered a temporary position as substitute teacher in a village school, a mile or so away. Thankful for this chance to practice her profession, she accepted, learning much from her brief experience. She then again applied for admission to the convent of the Daughters of the Sacred Heart, and might have been accepted, for her health was now much improved. However, the rector of the parish, Father Antonio Serrati, had been observing her ardent spirit of service and was making other plans for her future. He therefore advised the Mother Superior to turn her down once more.

Father Serrati, soon to be Monsignor Serrati, was to remain Francesca's lifelong friend and adviser. From the start he had great confidence in her abilities, and now he gave her a most difficult task. She was to go to a disorganized and badly run orphanage in the nearby town of Cadogno, called the House of Providence. It had been started by two wholly incompetent laywomen, one of whom had given the money for its endowment. Now Francesca was charged "to put things right," a large order in view of her youth-she was but twenty-four-and the complicated human factors in the situation. The next six years were a period of training in tact and diplomacy, as well as in the everyday, practical problems of running such an institution. She worked quietly and effectively, in the face of jealous opposition, devoting herself to the young girls under her supervision and winning their affection and cooperation. Francesca assumed the nun's habit, and in three years took her vows. By this time her ecclesiastical superiors were impressed by her performance and made her Mother Superior of the institution. For three years more she carried on, and then, as the foundress had grown more and more erratic, the House of Providence was dissolved. Francesca had under her at the time seven young nuns whom she had trained. Now they were all homeless.

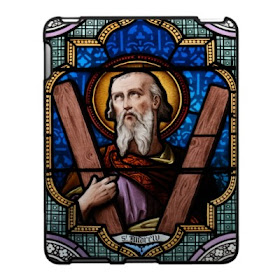

At this juncture the bishop of Lodi sent for her and offered a suggestion that was to determine the nun's life work. He wished her to found a missionary order of women to serve in his diocese. She accepted the opportunity gratefully and soon discovered a house which she thought suitable, an abandoned Franciscan friary in Cadogno. The building was purchased, the sisters moved in and began to make the place habitable. Almost immediately it became a busy hive of activity. They received orphans and foundlings, opened a day school to help pay expenses, started classes in needlework and sold their fine embroidery to earn a little more money. Meanwhile, in the midst of superintending all these activities, Francesca, now Mother Cabrini, was drawing up a simple rule for the institute. As one patron, she chose St. Francis de Sales, and as another, her own name saint, St. Francis Xavier. The rule was simple, and the habit she devised for the hard-working nuns was correspondingly simple, without the luxury of elaborate linen or starched headdress. They even carried their rosaries in their pockets, to be less encumbered while going about their tasks. The name chosen for the order was the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart.

With the success of the institute and the growing reputation of its young founder, many postulants came asking for admission, more than the limited quarters could accommodate. The nuns' resources were now, as always, at a low level; nevertheless, expansion seemed necessary. Unable to hire labor, they undertook to be their own builders. One nun was the daughter of a bricklayer, and she showed the others how to lay bricks. The new walls were actually going up under her direction, when the local authorities stepped in and insisted that the walls must be buttressed for safety. The nuns obeyed, and with some outside help went on with the job, knowing they were working to meet a real need. The townspeople could not, of course, remain indifferent in the face of such determination. After two years another mission was started by Mother Cabrini, at Cremona, and then a boarding school for girls at the provincial capital of Milan. The latter was the first of many such schools, which in time were to become a source of income and also of novices to carry on the ever-expanding work. Within seven years seven institutions of various kinds, each founded to meet some critical need, were in operation, all staffed by nuns trained under Mother Cabrini.

In September, 1887, came the nun's first trip to Rome, always a momentous event in the life of any religious. In her case it was to mark the opening of a much broader field of activity. Now, in her late thirties, Mother Cabrini was a woman of note in her own locality, and some rumors of her work had undoubtedly been carried to Rome. Accompanied by a sister, Serafina, she left Cadogno with the dual purpose of seeking papal approval for the order, which so far had functioned merely on the diocesan level, and of opening a house in Rome which might serve as headquarters for future enterprises. While she did not go as an absolute stranger, many another has arrived there with more backing and stayed longer with far less to show.

Within two weeks Mother Cabrini had made contacts in high places, and had several interviews with Cardinal Parocchi, who became her loyal supporter, with full confidence in her sincerity and ability. She was encouraged to continue her foundations elsewhere and charged to establish a free school and kindergarten in the environs of Rome. Pope Leo XIII received her and blessed the work. He was then an old man of seventy-eight, who had occupied the papal throne for ten years and done much to enhance the prestige of the office. Known as the "workingman's Pope" because of his sympathy for the poor and his series of famous encyclicals on social justice, he was also a man of scholarly attainments and cultural interests. He saw Mother Cabrini on many future occasions, always spoke of her with admiration and affection, and sent contributions from his own funds to aid her work.

A new and greater challenge awaited the intrepid nun, a chance to fulfill the old dream of being a missionary to a distant land. A burning question of the day in Italy was the plight of Italians in foreign countries. As a result of hard times at home, millions of them had emigrated to the United States and to South America in the hope of bettering themselves. In the New World they were faced with many cruel situations which they were often helpless to meet. Bishop Scalabrini had written a pamphlet describing their misery, and had been instrumental in establishing St. Raphael's Society for their material assistance, and also a mission of the Congregation of St. Charles Borromeo in New York. Talks with Bishop Scalabrini persuaded Mother Cabrini that this cause was henceforth to be hers.

A new and greater challenge awaited the intrepid nun, a chance to fulfill the old dream of being a missionary to a distant land. A burning question of the day in Italy was the plight of Italians in foreign countries. As a result of hard times at home, millions of them had emigrated to the United States and to South America in the hope of bettering themselves. In the New World they were faced with many cruel situations which they were often helpless to meet. Bishop Scalabrini had written a pamphlet describing their misery, and had been instrumental in establishing St. Raphael's Society for their material assistance, and also a mission of the Congregation of St. Charles Borromeo in New York. Talks with Bishop Scalabrini persuaded Mother Cabrini that this cause was henceforth to be hers.

In America the great tide of immigration had not yet reached its peak, but a steady stream of hopeful humanity from southern Europe, lured by promises and pictures, was flowing into our ports, with little or no provision made for the reception or assimilation of the individual components. Instead, the newcomers fell victim at once to the prejudices of both native-born Americans and the earlier immigrants, who had chiefly been of Irish and German stock. They were also exploited unmercifully by their own padroni, or bosses, after being drawn into the roughest and most dangerous jobs, digging and draining, and the almost equally hazardous indoor work in mills and sweatshops. They tended to cluster in the overcrowded, disease-breeding slums of our cities, areas which were becoming known as "Little Italies." They were in America, but not of it. Both church and family life were sacrificed to mere survival and the struggle to save enough money to return to their native land. Cut off from their accustomed ties, some drifted into the criminal underworld. For the most part, however, they lived forgotten, lonely and homesick, trying to cope with new ways of living without proper direction. "Here we live like animals," wrote one immigrant; "one lives and dies without a priest, without teachers, and without doctors." All in all, the problem was so vast and difficult that no one with a soul less dauntless than Mother Cabrini's would have dreamed of tackling it.

After seeing that the new establishments at Rome were running smoothly and visiting the old centers in Lombardy, Mother Cabrini wrote to Archbishop Corrigan in New York that she was coming to aid him. She was given to understand that a convent or hostel would be prepared, to accommodate the few nuns she would bring.

Unfortunately there was a misunderstanding as to the time of her arrival, and when she and the seven nuns landed in New York on March 31, 1889, they learned that there was no convent ready. They felt they could not afford a hotel, and asked to be taken to an inexpensive lodging house. This turned out to be so dismal and dirty that they avoided the beds and spent the night in prayer and quiet thought. But the nuns were young and full of courage; from this bleak beginning they emerged the next morning to attend Mass. Then they called on the apologetic archbishop and outlined a plan of action. They wished to begin work without delay. A wealthy Italian woman contributed money for the purchase of their first house, and before long an orphanage had opened its doors there. So quickly did they gather a house full of orphans that their funds ran low; to feed the ever-growing brood they must go out to beg. The nuns became familiar figures down on Mulberry Street, in the heart of the city's Little Italy. They trudged from door to door, from shop to shop, asking for anything that could be spared—food, clothing, or money.

With the scene surveyed and the work well begun, Mother Cabrini returned to Italy in July of the same year. She again visited the foundations, stirred up the ardor of the nuns, and had another audience with the Pope, to whom she gave a report of the situation in New York with respect to the Italian colony. Also, while in Rome, she made plans for opening a dormitory for normal-school students, securing the aid of several rich women for this enterprise. The following spring she sailed again for New York, with a fresh group of nuns chosen from the order. Soon after her arrival she concluded arrangements for the purchase from the Jesuits of a house and land, now known as West Park, on the west bank of the Hudson. This rural retreat was to become a veritable paradise for children from the city's slums. Then, with several nuns who had been trained as teachers, she embarked for Nicaragua, where she had been asked to open a school for girls of well-to-do families in the city of Granada. This was accomplished with the approbation of the Nicaraguan government, and Mother Cabrini, accompanied by one nun, started back north overland, curious to see more of the people of Central America. They traveled by rough and primitive means, but the journey was safely achieved. They stopped off for a time in New Orleans and did preparatory work looking to the establishment of a mission. The plight of Italian immigrants in Louisiana was almost as serious as in New York. On reaching New York she chose a little band of courageous nuns to begin work in the southern city. They literally begged their way to New Orleans, for there was no money for train fare. As soon as they had made a very small beginning, Mother Cabrini joined them. With the aid of contributions, they bought a tenement which became known as a place where any Italian in trouble or need could go for help and counsel. A school was established which rapidly became a center for the city's Italian population. The nuns made a practice too of visiting the outlying rural sections where Italians were employed on the great plantations.

The year that celebrated the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus' voyage of discovery, 1892, marked also the founding of Mother Cabrini's first hospital. At this time Italians were enjoying more esteem than usual and it was natural that this first hospital should be named for Columbus. Earlier Mother Cabrini had had some experience of hospital management in connection with the institution conducted by the Congregation of St. Charles Borromeo, but the new one was to be quite independent. With an initial capital of two hundred and fifty dollars, representing five contributions of fifty dollars each, Columbus Hospital began its existence on Twelfth Street in New York. Doctors offered it their services without charge, and the nuns tried to make up in zeal what they lacked in equipment. Gradually the place came to have a reputation that won for it adequate financial support. It moved to larger quarters on Twentieth Street, and continues to function to this day.

Mother Cabrini returned to Italy frequently to oversee the training of novices and to select the nuns best qualified for foreign service. She was in Rome to share in the Pope's Jubilee, celebrating his fifty years as a churchman. Back in New York in 1895, she accepted the invitation of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires to come down to Argentina and establish a school. The Nicaraguan school had been forced to close its doors as a result of a revolutionary overthrow of the government, and the nuns had moved to Panama and opened a school there. Mother Cabrini and her companion stopped to visit this new institution before proceeding by water down the Pacific Coast towards their destination. To avoid the stormy Straits of Magellan they had been advised to make the later stages of the journey by land, which meant a train trip from the coast to the mountains, across the Andes by mule-back, then another train trip to the capital. The nuns looked like Capuchin friars, for they wore brown fur-lined capes. On their unaccustomed mounts, guided by muleteers whose language they hardly understood, they followed the narrow trail over the backbone of the Andes, with frightening chasms below and icy winds whistling about their heads. The perilous crossing was made without serious mishap. On their arrival in Buenos Aires they learned that the archbishop who had invited them to come had died, and they were not sure of a welcome. It was not long, however, before Mother Cabrini's charm and sincerity had worked their usual spell, and she was entreated to open a school. She inspected dozens of sites before making a choice. When it came to the purchase of land she seemed to have excellent judgment as to what location would turn out to be good from all points of view. The school was for girls of wealthy families, for the Italians in Argentina were, on the average, more prosperous than those of North America. Another group of nuns came down from New York to serve as teachers. Here and in similar schools elsewhere, today's pupils became tomorrow's supporters of the foundations.

Not long afterward schools were opened in Paris, in England, and in Spain, where Mother Cabrini's work had the sponsorship of the queen. From the Latin countries in course of time came novice teachers for the South American schools. Another southern country, Brazil, was soon added to the lengthening roster, with establishments at Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. Back in the United States Mother Cabrini started parochial schools in and around New York and an orphanage at Dobbs Ferry. In 1899 she founded the Sacred Heart Villa on Fort Washington Avenue, New York, as a school and training center for novices. In later years this place was her nearest approach to an American home. It is this section of their city that New Yorkers now associate with her, and here a handsome avenue bears her name.

Not long afterward schools were opened in Paris, in England, and in Spain, where Mother Cabrini's work had the sponsorship of the queen. From the Latin countries in course of time came novice teachers for the South American schools. Another southern country, Brazil, was soon added to the lengthening roster, with establishments at Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. Back in the United States Mother Cabrini started parochial schools in and around New York and an orphanage at Dobbs Ferry. In 1899 she founded the Sacred Heart Villa on Fort Washington Avenue, New York, as a school and training center for novices. In later years this place was her nearest approach to an American home. It is this section of their city that New Yorkers now associate with her, and here a handsome avenue bears her name.

Launching across the country, Mother Cabrini now extended her activities to the Pacific Coast. Newark, Scranton, Chicago, Denver, Seattle, Los Angeles, all became familiar territory. In Colorado she visited the mining camps, where the high rate of fatal accidents left an unusually large number of fatherless children to be cared for. Wherever she went men and women began to take constructive steps for the remedying of suffering and wrong, so powerful was the stimulus of her personality. Her warm desire to serve God by helping people, especially children, was a steady inspiration to others. Yet the founding of each little school or orphanage seemed touched by the miraculous, for the necessary funds generally materialized in some last-minute, unexpected fashion.

In Seattle, in 1909, Mother Cabrini took the oath of allegiance to the United States and became a citizen of the country. She was then fifty-nine years old, and was looking forward to a future of lessened activity, possibly even to semi-retirement in the mother house at Cadogno. But for some years the journeys to and fro across the Atlantic went on; like a bird, she never settled long in one place. When she was far away, her nuns felt her presence, felt she understood their cares and pains. Her modest nature had always kept her from assuming an attitude of authority; indeed she even deplored being referred to as "head" of her Order. During the last years Mother Cabrini undoubtedly pushed her flagging energies to the limit of endurance. Coming back from a trip to the Pacific Coast in the late fall of 1917, she stopped in Chicago. Much troubled now over the war and all the new problems it brought, she suffered a recurrence of the malaria contracted many years before. Then, while she and other nuns were making preparations for a children's Christmas party in the hospital, a sudden heart attack ended her life on earth in a few minutes. The date was December 22, and she was sixty-seven. The little nun had been the friend of three popes, a foster-mother to thousands of children, for whom she had found means to provide shelter and food; she had created a flourishing order, and established many institutions to serve human needs.

It was not surprising that almost at once Catholics in widely separated places began saying to each other, "Surely she was a saint." This ground swell of popular feeling culminated in 1929 in the first official steps towards beatification. Ten years later she became Blessed Mother Cabrini, and Cardinal Mundelein, who had officiated at her funeral in Chicago, now presided at the beatification. Heralded by a great pealing of the bells of St. Peter's and the four hundred other churches of Rome, the canonization ceremony took place on July 7, 1946. Hundreds of devout Catholics from the United States were in attendance, as well as the highest dignitaries of the Church and lay noblemen. Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini, the first American to be canonized, lies buried under the altar of the chapel of Mother Cabrini High School in New York City.

.jpg)