VATICAN CITY, APRIL 9, 2008 Zenit

Here is a translation of the address Pope Benedict XVI gave April 9, 2008 at the general audience in St. Peter's Square. This is a great read for all men and women conversing with the Lord about the possibility of a religious vocation.

* * *

Dear brothers and sisters,Today I would like to talk about St. Benedict, the father of Western monasticism, and also the patron saint of my papacy. I will begin with a few words from Pope St. Gregory the Great who wrote the following about St. Benedict: “The man of God who shone on this earth with so many miracles does not shine any less for the eloquence with which he knew how to present his teaching” (Dial. II, 36).

The Great Pope wrote these words in the year 592: The holy monk had died barely 50 years earlier and was still alive in the memories of the people and above all in the blossoming religious order he founded. St. Benedict, through his life and work, had a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture.

The most important source of information on his life is the second book of the Dialogues by Pope St. Gregory the Great. It is not a biography as such. According to the ideas of the time, he wanted to demonstrate by using a real person -- St. Benedict -- how someone who abandons himself to God can reach the heights of contemplation. He offers us a model of human life characterized as an ascent toward the peak of perfection.

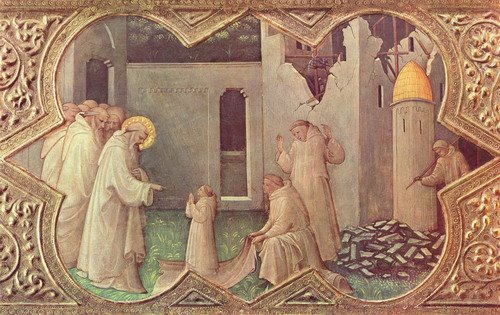

Pope St. Gregory the Great tells us in the book of the Dialogues about the many miracles performed by the saint. Here too he did not want to simply recount a strange event, but rather demonstrate how God, by warning, helping and even punishing, intervenes in real situations in the life of man. He wanted to show that God is not a distant hypothesis situated at the beginning of the world, but rather that he is present in the life of man, of all men.

This perspective of the "biography" is also explained in the light of the general context of the times: Between the fifth and sixth centuries the world suffered a terrible crisis in values and institutions, caused by the collapse of the Roman Empire, the invasion of new people and the decline of customs. By presenting St. Benedict as a "shining light," Gregory wanted to show the way out of “this dark night of history” (cfr. John Paul II, Teachings, II/1, 1979, p. 1158), the terrible situation here in the city of Rome.

In fact, the work of St. Benedict and his Rule in particular are bearers of a genuine spiritual turmoil, which changed the face of Europe over the centuries and whose effects were felt way beyond his time and the borders of his own country. Following the collapse of the political unity created by the Roman Empire, it revived a new spiritual and cultural unity -- that of Christian faith, shared among the people of the Continent. This is how the Europe we know today was born.

The birth of St. Benedict is dated around the year 480. He was born, according to Pope St. Gregory, “ex provincia Nursiae” -- in the region of Norcia. His parents were well off and sent him to be educated in Rome. He did not stay long in the eternal city however. Pope St. Gregory offers a very likely explanation for this. He points out that the young Benedict was disgusted by the way of life of many of his fellow students who led unprincipled lives and he did not want to fall into the same trap. He wanted only to please God “soli Deo placere desiderans” (II Dial., Prol 1).

Therefore, even before he completed his studies, Benedict left Rome and withdrew to the solitude of the mountains east of Rome. Initially he stayed in the village of Effide (now: Affile), where for some time he affiliated himself with a "religious community" of monks, and then became a hermit living in Subiaco, which was close by. For three years he lived completely alone in a cave there. In the High Middle Ages, this cave became the "heart" of a Benedictine monastery called "Sacro Speco." His time in Subiaco was a period of solitude spent with God and was for Benedict a time in which he matured.

Here he endured and overcame the three fundamental human temptations: the temptation of self-assertion and the desire to place oneself at the center of things; the temptation of the senses; and finally, the temptation of anger and revenge.

Benedict firmly believed that only after conquering these temptations would he be able to say anything useful to others in need. And so, having pacified his soul, he was fully able to control the drive to put oneself first, and so became a creator of peace. Only then did he decide to found his first monasteries in the valley of Anio, near Subiaco.

In the year 529 he left Subiaco to establish himself in Montecassino. Some have explained this move as a flight from the interference of a jealous local clergyman, but this is not likely, as the priest's sudden death did not lead Benedict to move back again (II Dial. 8). In truth, he took this decision because he had entered into a new phase of monastic experience and personal maturity.

According to Gregory the Great his exodus from the remote valley of Anio to Mount Cassio -- which dominates the vast planes around it -- is symbolic of his character. A monastic life of isolation has it's place, but a monastery also has a public aim in the life of the Church and society as a whole. It must serve to make faith visible as a force of life. In fact, when Benedict died on March 21, 547, through his Rule and the Benedictine order that he founded, he left us a legacy that bore fruit all over the world in the subsequent centuries, and continues to do so today.

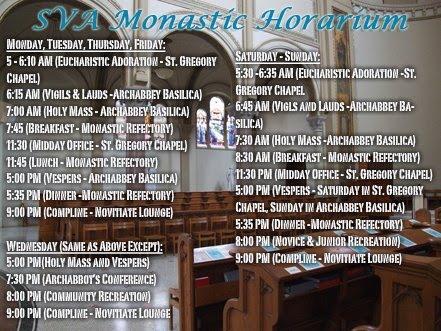

In the whole of the second book of the Dialogues, Gregory shows us how the life of St. Benedict was immersed in an atmosphere of prayer, the foundation of his existence. Without prayer you cannot experience God. Benedict's spirituality was not cut off from reality. In the turmoil and confusion of the times, Benedict lived under the gaze of God. He never lost sight of the duties of everyday life and of man and his necessities. In seeing God he understood the reality of man and his mission. In his Rule he explains monastic life as “a school at the service of the Lord” (Prol. 45), and he asks his monks "not to place anything ahead of the work of God" (that is, the Divine Office and the Liturgy of the Hours)(43,3). He underlines, however, that the act of prayer is in the first instance the act of listening (Prol. 9-11), which is then translated into concrete action. “Every day the Lord expects us to respond to his holy teaching with action” (Prol. 35).

The life of a monk therefore becomes a fruitful symbiosis of action and contemplation, “so that God is glorified in everything” (57,9). In contrast to an egocentric and easy self-fulfillment, often extolled today, the first and irrefutable duty of a disciple of St. Benedict is a sincere search for God (58,7) on the road traced by a humble and obedient Christ (5,13), the love of whom nothing should be allowed to stand in the way (4,21; 72,11).

It is in this way, in serving others, that Benedict becomes a man of service and peace. By showing obedience through his actions with a faith driven by love (5,2), the monk acquires humility (5,1), to which the Rule dedicates a whole chapter (7). In this way man becomes more like Christ and attains true self-fulfillment as a creature in God's own image.

The obedience of the disciple must be matched by the wisdom of the Abbot, who “takes the place of Christ” (2,2; 63,13) in a monastery. His role, outlined mainly in the second chapter of the Rule, with a description of spiritual beauty and demanding commitment, can be considered a self-portrait of Benedict, since, as Gregory the Great writes, “the Saint could not teach what he himself had not lived” (Dial. II, 36). The Abbot must be both a loving father and a strict teacher (2,24), a true educator.

Inflexible when it comes to vices, he is called upon to imitate the tenderness of the Good Shepherd (27,8) to “assist rather than dominate” (64,8), to “point out more with actions than words all that is good and holy,” and to “ illustrate the divine commandments by setting an example” (2,12).

In order to be capable of making responsible decisions, the Abbot must also be someone who listens to “the advice of his brothers” (3,2), because “God often reveals the most apt solution to the youngest person” (3,3). This attitude makes the Rule, written almost 15 centuries ago very current! A man with public responsibility, even in small circles, must always be a man who knows how to listen and to learn from what he hears.

Benedict describes the Rule as “minimal, just an initial outline” (73,8); in reality, however, it offers useful advice not only to monks, but to anyone looking for guidance on the path to God. Through his capacity, his humanity, and his sober ability to discern between what is essential and what is secondary in the spiritual life, he is still a guiding light today.

Paul VI, by proclaiming St. Benedict the patron saint of Europe on October 24, 1964, recognized the wonderful work accomplished by the saint through the Rule toward creating the civilization and culture of Europe.

Today, Europe -- deeply wounded during the last century by two world wars and the collapse of great ideologies now revealed as tragic utopias -- is searching for it's own identity. A strong political, economic and legal framework is undoubtedly important in creating a new, unified and lasting state, but we also need to renew ethical and spiritual values that draw on the Christian roots of the Continent, otherwise we cannot construct a new Europe.

Without this vital lifeblood, man remains exposed to the ancient temptation of self-redemption -- a utopia, which caused in various ways in 20th-century Europe, as pointed out by Pope John Paul II, “an unprecedented regression in the tormented history of humanity” (Teachings, XIII/1, 1990, p. 58).

In the search for true progress, let us listen to the Rule of St. Benedict and see it as a guiding light for our journey. The great monk is still a true teacher in whose school we can learn the art of living a true humanism.